Kinderhook, New York

Kinderhook, New York | |

|---|---|

Main square in Kinderhook | |

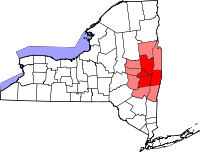

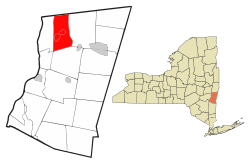

Location of Kinderhook, New York | |

| Coordinates: 42°24′46″N 73°40′53″W / 42.41278°N 73.68139°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| County | Columbia |

| Settled | 1750 |

| Established | 1788 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Town Council |

| • Town Supervisor | Tim Ooms (R) |

| • Town Council | Members' List |

| Area | |

• Total | 32.41 sq mi (83.95 km2) |

| • Land | 31.81 sq mi (82.38 km2) |

| • Water | 0.61 sq mi (1.57 km2) |

| Elevation | 239 ft (73 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 8,330 |

| • Density | 260/sq mi (99/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code | 12106 |

| Area code | 518 |

| FIPS code | 36-021-39573 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0979116 |

| Website | www |

Kinderhook is a town in the northern part of Columbia County, New York, United States. The population was 8,330 at the 2020 census,[2] making it the most populous municipality in Columbia County. The name of the town means "Children's Corner" in the language of the original Dutch settlers (Kinderhoek). The name "Kinderhook" has its root in the landing of Henry Hudson in the area around present-day Stuyvesant, where he was greeted by Native Americans with many children. With the Dutch kind meaning "child" and hoek meaning "corner", it could be that the name refers to a bend (or "corner") in the river where the children are. The eighth president of the United States, Martin Van Buren, was born in Kinderhook and retired to it.

The town of Kinderhook contains two villages, one of which is also named Kinderhook; the other is the village of Valatie. In addition, the town contains the hamlet of Niverville, next to Kinderhook Lake.

History

[edit]In 1609 Henry Hudson sailed as far north as Kinderhook on his exploration of the Hudson River and named the location "Kinderhoek".[3] Kinderhook signifies in the Dutch tongue "the children's corner", and is supposed to have been applied to this locality, in 1609, on account of the many Indian children who had assembled on one of the bluffs along the river to see his strange vessel (the Half Moon) sailing upstream.[4] Hudson had mixed dealing with the local Mohican natives, ranging from peaceful trade to minor skirmishes. As the Dutch attempted to colonize the area, further warfare broke out with the natives. Another version says that a Swede named Scherb, living in the forks of an Indian trail in the present town of Stuyvesant, had such a numerous family of children that the name of Kinderhook was used by the Dutch traders to designate that locality.[citation needed] A third theory about the town's name derives from a settler, named Frans Pietersz. Clauw, who operated a mill on the river and was known as the "child of luxury" ("Kind van Weelde").[5]

Kinderhook was settled before 1651[6] and established as a town in 1788[7] from a previously created district (1772), but lost substantial territory to form part of the town of Chatham in 1775. Kinderhook was one of the original towns of Columbia County. More of Kinderhook was lost to form the town of Ghent in 1818 and the town of Stuyvesant in 1823.[8]

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 32.4 square miles (83.9 km2), of which 31.8 square miles (82.4 km2) is land and 0.62 square miles (1.6 km2), or 1.87%, is water,[9] including Kinderhook Lake, Kinderhook Creek, and the waterfalls of Valatie.

The northern town line is the border of Rensselaer County.

Kinderhook Creek is an important stream in the town, flowing southwest toward tidal Stockport Creek, an arm of the Hudson River. U.S. Route 9 and New York State Route 9H pass through the town.

Arts and culture

[edit]President Martin Van Buren's retirement home, Lindenwald, is in the town of Kinderhook.[10][11] The Dutch Colonial Luykas Van Alen House, a National Historic Landmark (c.1737), is thought to be author Washington Irving's inspiration for the "Van Tassel family" farm in his classic story "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow", as Irving — a friend of Van Buren — was a frequent visitor and sometime resident to the area.[12] The 19th-century rural Ichabod Crane Schoolhouse, named for the Washington Irving character patterned after Kinderhook schoolteacher, Jesse Merwin, is adjacent to the Van Alen House.[13][14]

The Columbia County Historical Society is headquartered in the town, with four historic properties, including the 1737 Luykas Van Alen House, the 1850 Ichabod Crane Schoolhouse, the c1819 James Vanderpoel 'House of History', and the 1915 CCHS Museum & Library building. The Historical Society also owns and exhibits a permanent collection consisting of important and unique genealogical materials, archives, paintings, textiles, furniture and decorative arts relating to Columbia County's culture and heritage.

The James Vanderpoel House, known as "The House of History", on Broad Street in Kinderhook village was built circa 1819 and is an important example of high-style Federal architecture that is owned and maintained by the Columbia County Historical Society.[14][15] The Old Columbia Academy was an early Dutch school established on March 13, 1787. The school was renamed Kinderhook Academy on April 3, 1824.[7]

The former Martin Van Buren Public School, on Broad Street, now houses an international gallery of contemporary fine art, The School, a branch of the Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.[16][17]

The Olde Kinderhook Fair, also called the Kindercrafters Fair, is an annual arts and crafts fair held in the Kinderhook Village Square and sponsored by the Kinderhook Business and Professional Association.[18] Other activities are often scheduled for the fair day, such as the Kinderhook Memorial Library Book Sale, free tours of the James Vanderpoel House, and live music. The 42nd fair was held in June 2018.[19]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1820 | 3,963 | — | |

| 1830 | 2,706 | −31.7% | |

| 1840 | 3,512 | 29.8% | |

| 1850 | 3,970 | 13.0% | |

| 1860 | 4,331 | 9.1% | |

| 1870 | 4,055 | −6.4% | |

| 1880 | 4,200 | 3.6% | |

| 1890 | 3,709 | −11.7% | |

| 1900 | 3,333 | −10.1% | |

| 1910 | 2,947 | −11.6% | |

| 1920 | 2,935 | −0.4% | |

| 1930 | 3,104 | 5.8% | |

| 1940 | 3,094 | −0.3% | |

| 1950 | 3,284 | 6.1% | |

| 1960 | 4,185 | 27.4% | |

| 1970 | 5,688 | 35.9% | |

| 1980 | 7,674 | 34.9% | |

| 1990 | 8,112 | 5.7% | |

| 2000 | 8,300 | 2.3% | |

| 2010 | 8,498 | 2.4% | |

| 2020 | 8,330 | −2.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[2] | |||

As of the census of 2000, there were 8,296 people, 3,165 households, and 2,247 families residing in the town. The population density was 260.6 inhabitants per square mile (100.6/km2). There were 3,434 housing units at an average density of 107.9 per square mile (41.7/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 97.31% White, 0.68% Black or African American, 0.23% Native American, 0.86% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 0.33% from other races, and 0.57% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.41% of the population.[20]

There were 3,165 households, out of which 33.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 58.5% were married couples living together, 8.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.0% were non-families. 24.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.52 and the average family size was 3.01.[20]

In the town, the population was spread out, with 24.5% under the age of 18, 5.8% from 18 to 24, 27.2% from 25 to 44, 27.0% from 45 to 64, and 15.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.8 males.[20]

The median income for a household in the town was $52,604, and the median income for a family was $61,074. Males had a median income of $41,386 versus $27,880 for females. The per capita income for the town was $24,259. About 2.8% of families and 4.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 5.3% of those under age 18 and 4.4% of those age 65 or over.[20]

Government

[edit]As of 2019, Timothy Ooms was the Town Supervisor; April Pinkowski Town Clerk. The "Town Department" section of the Town of Kinderhook government website maintains current information on other town officials and governing bodies.[21]

Notable people

[edit]- John Faso, former U.S. representative from New York's 19th congressional district,[22] former New York State Assembly Minority Leader and failed candidate for comptroller (2002) and governor (2006)[23]

- Chris Gibson, former U.S. representative from New York's 20th congressional district[24]

- William S. Groesbeck, U.S. representative[25]

- Washington Irving, author, lived in the town of Kinderhook for about eight weeks in 1809 after the death of his fiancée; wrote portions of A History of New-York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty in Kinderhook[26]

- Mariela Jácome, athlete, played on Ecuador women's national football team during the 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup

- Jennie Jerome, mother of Winston Churchill, lived in Kinderhook after her father acquired Van Buren's home[27]

- Jesse Merwin, Kinderhook schoolteacher known to be the 'pattern' for the character Ichabod Crane, and longtime friend of Washington Irving; Merwin maintained correspondence with Irving for several decades (Merwin later retired from teaching and became an attorney).

- John Woodward Philip, naval officer during the Civil War and Spanish–American War[25]

- Donald L. Rutherford, 23rd Chief of Chaplains of the United States Army[25]

- Nicholas Sickles, U.S. representative[28]

- John Evert Van Alen, U.S. representative[29]

- Martin Van Buren, the eighth president of the United States, was born and lived in Kinderhook. His nickname "Old Kinderhook" may have given rise to the expression "OK" and its attendant hand gesture.[25] His maternal ancestral home, Hoes House, was built circa 1760 in the Village of Valatie.

- Cornelius P. Van Ness, 10th governor of Vermont[25]

- Peter Van Schaack, Kinderhook lawyer and notable British Loyalist during the American Revolution[30]

Communities and locations in the town

[edit]- Kinderhook – A village located on U.S. Route 9, southwest of the center of the town.

- Kinderhook Lake – A lake on the northeastern town line.

- Kinderhook Memorial Library – A public library serving the village of Kinderhook and parts of neighboring Stuyvesant.

- Knickerbocker Lake – A small lake in the northern part of the town near the intersection of U.S. Route 9 and County Road 28.

- Lindenwald (Martin Van Buren National Historic Site) – The final home of Martin Van Buren is in the southwestern section of the town.

- Niverville – A hamlet and census-designated place in the northeastern part of the town, south of Kinderhook Lake on County Road 28B and New York State Route 203.

- Valatie – A village located at the center of the town.

- Valatie Colony – A hamlet along County Road 28B north of Valatie village and southwest of Niverville.

Trivia

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2014) |

Moving pictures filmed in Kinderhook

[edit]- Films

- Pat Solitano played by Bradley Cooper in Silver Linings Playbook (2012), also starring Jennifer Lawrence and Robert De Niro, explains during a dinner scene the origin of the word "OK" and its Old Kinderhook roots.

- Meskada (2009) starring Nick Stahl, Rachel Nichols, and Kellan Lutz was shot partially in Valatie.

- The Cake Eaters (2006), a Mary Stuart Masterson film, was shot in Hudson, Stuyvesant, and Kinderhook.

- Hero Hero (2000), starring Alan Gelfant and Julianne Nicholson, was shot in Kinderhook.

- Part of the film The Age of Innocence (1993), starring Daniel Day-Lewis and Michelle Pfeiffer, was filmed at the Van Alen House.

- Haldane of the Secret Service (1923), starring escape artist Harry Houdini and Gladys Leslie, filmed at Beaver Kill Falls in Valatie village.

- Television

- The Sopranos character Pat Blundetto owned a farm said (in "All Due Respect") to be located at 146 Route 9A in Kinderhook, which figures prominently in multiple episodes, culminating in the Season 5 finale. Tony Blundetto (Tony Soprano's cousin), who was murdered at this location, mentions being called Ichabod Crane by others while visiting the farm as a teen.

- Peter Snyder, Father to Maura West, 3-Time Best Actress Daytime Emmy award winner (Daytime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series) (2007, 2010, 2015); (As The World Turns, The Young and the Restless, General Hospital etc.), was born and raised on Kinderhook Lake, in Niverville (hamlet) in the Town of Kinderhook, NY.

Music

[edit]- Rasputina's album Sister Kinderhook is centered around the Dutch colonial heritage of the town as well as that of other New Netherland settlements of New York.

Other

[edit]- One of the linguistic legends of the word "okay" has its origin during Martin Van Buren's campaign as an abbreviation of "Old Kinderhook", or "O.K."[31]

- The children of the American actor Sidney Poitier attended school in Kinderhook.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ "2016 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- ^ a b U.S. Census, 2020, 'Kinderhook town, Columbia County, New York'

- ^ Collier, Edward Augustus (1914). A History of Old Kinderhook from Aboriginal Days to the Present Time: Including the Story of the Early Settlers, Their Homesteads, Their Traditions, and Their Descendants; with an Account of Their Civic, Social, Political, Educational, and Religious Life. G. P. Putnam's Sons. p. 2. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ "Town of Kinderhook New York". Town of Kinderhook, New York. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ^ A Note on Frans Pietersz Clauw: L by Dr. Wilson O. Clough, Professor Emeritus, University of Wyoming. pg. 9, http://www.hollandsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/deHalveMaen_1964-01_XXXVIII_04-Red.pdf

- ^ Edward A Collier, D.D., A History of Old Kinderhook. G.P. Putman & Sons, 1914, p.44

- ^ a b "Points of Interest". Town of Kinderhook New York. Archived from the original on July 26, 2014. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ "History". Columbia County, New York. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Kinderhook town, Columbia County, New York". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ^ "Martin Van Buren National Historic Site". National Park Service. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ "Martin Van Buren National Historic Site, Lindenwald, New York". National Park Service. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ "Van Alen House receives $2.25K for new signs". Columbia-Greene Media. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ "Columbia County Historical Sites". Columbia County. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ a b Buff, Sheila (2009). Insiders' Guide® to the Hudson River Valley. Globe Pequot. p. 26. ISBN 9780762755691. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ "James Vanderpoel House". Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ Hallenbeck, Brent (February 25, 2016). "Going Home, new Weekend feature: Columbia County, N.Y.". Section: "Kinderhook". The Burlington Free Press. burlingtonfreepress.com. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ "About the Gallery". Jack Shainman Gallery. jackshainman.com. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ "Kinderhook Business & Professional Association (KBPA)". Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ "Olde Kinderhook Fair in Kinderhook". Louis Marquette. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Town of Kinderhook, NY - Town Departments". Town of Kinderhook, NY. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ "Faso, John J., (1952 - )". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ^ "An Ill-Timed Candidate Believes His Time Is Now". The New York Times. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ "Gibson, Christopher (1964 - )". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Kinderhook, New York". City-Data.com. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ "Connecticut's Sleepy Hollow". ConnecticutHistory.org. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ "Martin Van Buren Slept Here". The New York Times. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ "Sickles, Nicholas (1801 - 1845)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ "Van Alen, John Evert (1749 - 1807)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved July 31, 2014.

- ^ Newman, Roger K. (2009). The Yale Biographical Dictionary of American Law. Yale University Press. p. 560. ISBN 978-0300113006. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ Ciardi, John. "Martin Van Buren Was OK". NPR. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

External links

[edit]- Town of Kinderhook official website

- Village of Kinderhook

- Village of Valatie

- Martin Van Buren Historic Site

- Luykas Van Alen House Historical Museum

- Historic information about Kinderhook

- Some Kinderhook History from "Kinderhook Connection"

- Kinderhook Memorial Library

- Hudson Valley Vernacular Architecture

- A History of Old Kinderhook, by Edward A. Collier. Originally published by the Knickerbocker Press, New York, 1914.

- Profile for Kinderhook, NY at ePodunk